- On the Italian Stage

Eduardo De Filippo’s Theater

Part 2

View details about the event: Eduardo De Filippo’s Theater

An Artist's Paper Life

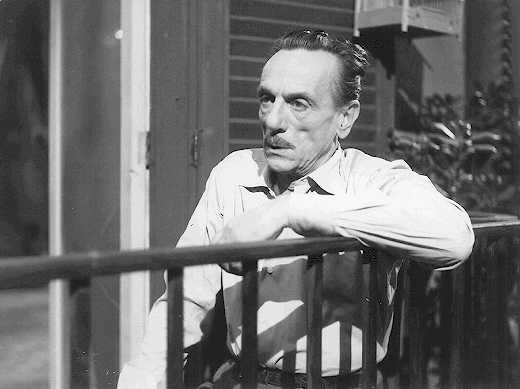

Leo Yeni

An Artist’s Paper Life

Curated by Cynthia Madansky

In collaboration with Centro Primo Levi

On view through February 26

Mon-Fri 10-6

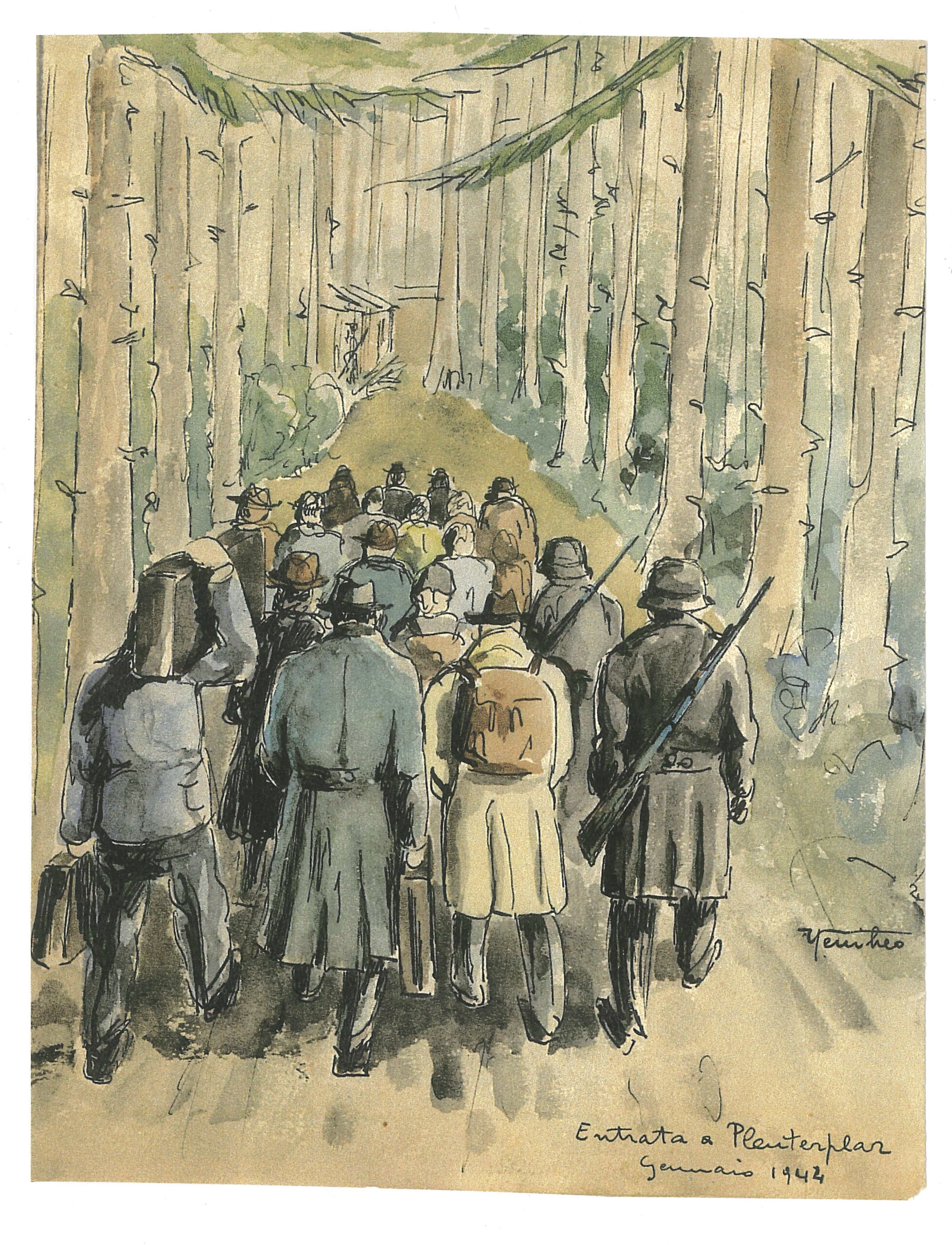

An exhibition of drawings from the internment camp, sketchbooks with notations on architecture, art history and decorative arts, sketches, paintings, family photographs and official papers.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

Leo Yeni was 23 year old in 1943, when Italy surrendered to the Allies and precipitated into chaos and a civil war.

The journey that would eventually take him to New York along with thousands of refugees and survivors, begins in Milan where, as a young man, he studied at the Art Academy of Brera. He learned to love art and, in the nationalistic narrative of the Regime, learned that Art was Italian and rooted in the splendors of ancient Rome and, secondarily, ancient Greece.

Italy and Greece were Leo’s parents’ birthplaces, as well as the references of hundreds of art notes and sketches that he jotted on paper wherever he could, during his school years, after his expulsion from the academy in 1938 and then, during his flight to Switzerland after September 8th, 1943.

Made of paper were also hundreds of notifications, registrations, certificates, police reports, ministerial decrees, entry and exit notices, that defined the Yenis’ as individuals who existed outside of the protection accorded by the law to citizens and could easily be erased and leave no trace. They could work, go to school, consolidate strong friendships, but their lives were ultimately paper ones. This notion is borrowed from Anna Pizzuti’s seminal study in foreign Jews in Italy Vite di Carta.

Leo Yeni was born in Italy in 1920. His father, Isac Yeni had moved there from Salonika in 1912, following the beginning of the Italian-Turkish war. He made a career as an accountant at the Banca Commerciale Italian. His mother, Pia Della Torre was Italian, born in Livorno. Her family had lived in Tuscany for centuries. As established by the Italian law until 1948, Pia had lost her citizenship after marrying Isac in 1917. At the time, it may have not made much of a difference to the couple.

A 2010 certificate of the citizens registry of Milan indicates that her name was removed from the city census in 1954, due to the “accertata irreperibilità,” “the verified impossibility to locate the above-mentioned Greek citizen.

Something had gone astray in the Italian paper trail. In fact, according to official documents, in 1938, when Mussolini and the King promulgated the race laws against the Jews, along with some 50,000 Jews, the Yenis’ lost their means of livelihood and the rights that made them similar to citizens but not quite the same. As foreign Jews, they were expelled and asked to leave the country by March 12, 1939. As many who did not have anywhere to go, they remained and, later on, moved to the countryside where their presence would be less conspicuous.

Still according to public records, Pia and Isac were arrested near Varese in 1944, detained in Milan and deported to Auschwitz where they were both killed. She was 63, Isac 75.

A few days before the arrest, the family was organizing Leo’s departure for Switzerland. Crossing the border was difficult, dangerous and onerous. After November 1943, when the police of the Italian Social Republic issued the arrest warrant against all Jews present on Italian territory, thousands of people found themselves stranded at the mercy of Fascist and Nazi manhunt.

In the turmoil that followed the armistice, Jews, who had been singled out in the persecution of the rights in 1938, were now part of a much larger group of civilians, prisoners of war, deserters, partisans, anti-fascists, and even fascist criminals seeking to elude justice or reprisal. Large survival networks emerged to serve many categories of people. Government authorities, police and many civilians supported Mussolini’s Republican rule and collaborated with all German operations. On the other hand, ruthless German violence against the weakest strata of the population contributed to create antagonistic sentiments toward the former ally turned occupier. Fugitives competed over preferred channels of escape. Crossing the Swiss border was one of them.

Among 44,000 Italians who found refuge in Switzerland, including civilians and military, there were about 4,500 Jews. Many others however, were either rejected by the Swiss or sold by the guides they had hired for the often impervious crossing.

In this circumstance, Leo Yeni prepared himself to take the road to Lugano and Bellinzona from the mountain area near Varese where the family had taken lodging. In his diary, he describes in detail the preparation and the farewell to the parents, his aunt and their landlady.

In Switzerland, Isac had a cousin, Isac de Abravanel, who could help Leo, who had already miraculously escaped a major roundup.

With the initial help of a guide and a map with a few landmarks, Leo crossed the mountains covered with snow. After a few days of traveling, he lost his way and ended up on the Italian side of the border, swarmed by Fascist militia and Germans SS. A few lucky encounters enabled him to hide for the night. He decided that it would be safer to go back. When he arrived at the home where his parents were staying, he learned that they had just been arrested.

He began preparing his second trip, this time with a guide all the way to Lugano where he finally arrived. Through the help of his uncle, Leo found lodging. He had no other choice but to report to the police and request to be interned in a refugee camp. He was first arrested and briefly placed in jail. After his request of asylum was approved, he was transferred to a temporary camp in Bellinzona and, finally, to the internment camp of Unterwalden.

In internment, Leo conquered a space for himself to continue to draw and write, documenting day by day, on paper, as drawings or text, events, human relations, emotions, aspirations that flourished and quiver in the small world of the camp set apart from all societies.

In 1945, Leo was admitted at the Ecole d’Art La Chaux-De-Fonds where he studied etching and other artistic techniques.

After the war ended, he had no family, no country and wanted to continue his work as an artist. The possibility to obtain Italian citizenship was remote. At the imposition of the Allies, Italy had reluctantly received thousands of refugees. The search for the deportees began as soon as Rome was liberated and the magnitude of the deportation of the Jews was beginning to emerge in Italy even before the rest of Europe was liberated.

Through Hias, Leo was offered the opportunity to emigrate to the US. In January 1946, his friend Dante, whom he had met at Camp Unterwalden, wrote to him: “Going to America, would be a marvelous gain for you. You lose nothing not to return to Italy. […] Listen to your old Dante, go to America and, if you can’t, try to stay in Switzerland. It will take years before things improve here. I feel rather down, in a way, it was better when it was worse. My wishes were all about returning to Italy. Now, all I would like is to leave. Goodbye, my dear Leo, all best to you.”

Leo Yeni moved to the US in 1946 and established himself as a designer and artist.